Sif Brookes

–

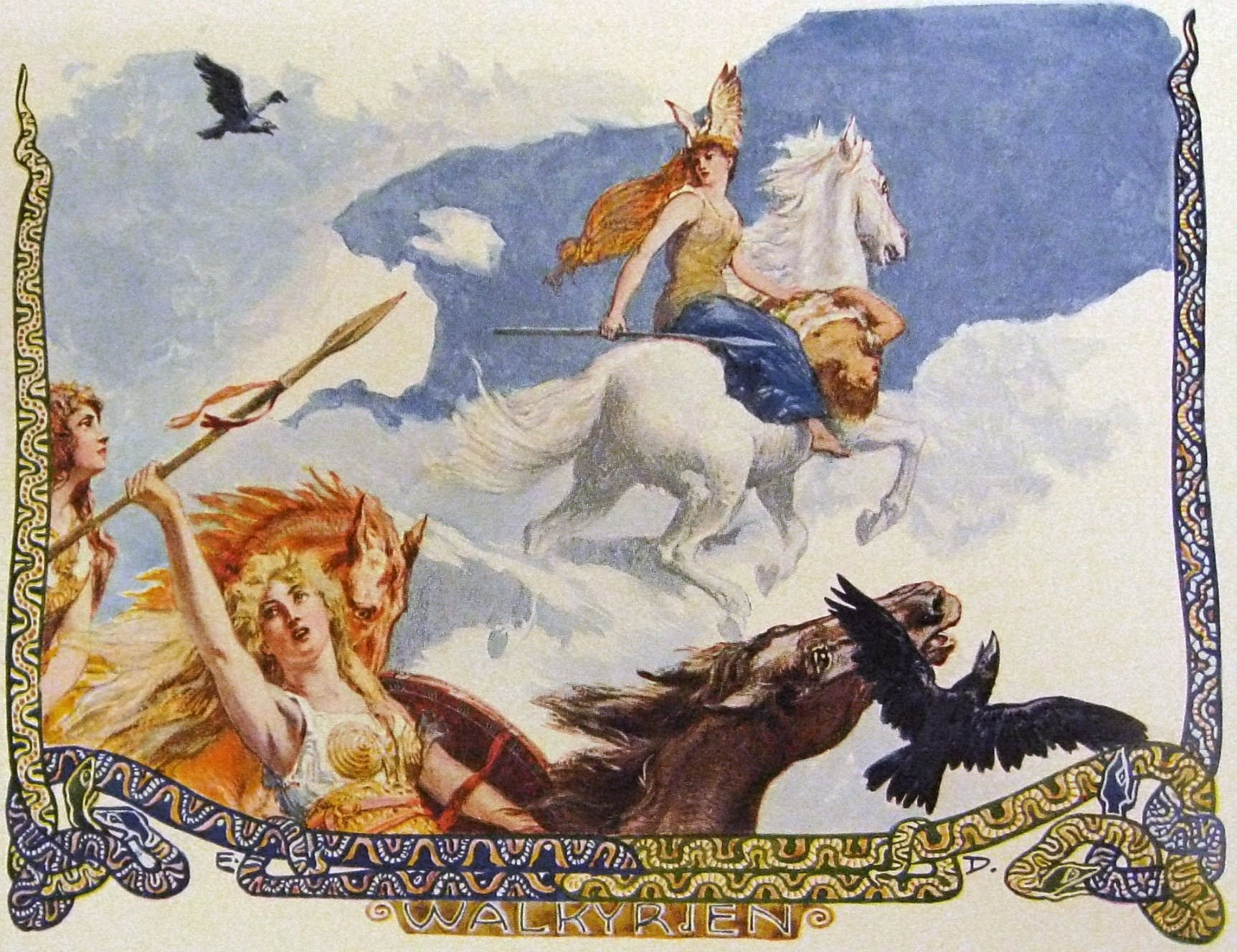

Choosers of the Slain. Slaughter-eager goddesses of the battle-fire. Carnage Maidens.

Wives of Heroes. Mead Bearers. Wise Counsel.

The duality of the Valkyrie (‘Chooser of the Slain’) is an area of much discussion in academic spaces, with many trying to reconcile these two very distinct depictions into a cohesive whole. I’ve long held the position that this dichotomy isn’t an anomaly in the Nordic space, with many of our gods being defined by apparent contradiction. For instance, Odin is of frenzy and of poetry, while Freyja is of war and of love.

But being one thing and another is to be in a liminal space ‘between’. A place outside of perceived boundaries. Being between two worlds, crossing boundaries, breaking social conventions, or being between two states of being was a place that often resulted in the attainment of power, wisdom, or knowledge.

As psychopomps, as travellers between Asgard and Midgard, as feminine beings engaging in bloodthirsty acts in the culturally perceived masculine realm of battle and war, as magic users, as (on occasion) empowered humans, as death deities that walk the living earth, the Valkyries I would argue, are exemplars of this phenomenon. They are the guardians of two distinct worlds, life and death, and they act in ways that accelerate a person’s journey over that threshold, or bar them from entry.

However, this perspective is one we’ve been gifted in hindsight, looking back at history some thousand years removed. In truth, the duality of the Valkyrie was an image that revealed itself slowly over a period of 400 or so years, driven by a cultural shift from pagan beliefs into the Christian religion. It’s a story of euhemerism, and of gradually stripping divinity from the supernatural and the ‘other’.

When it comes to the Valkyries, their earliest depictions tend towards behaviours defined by animalistic behaviour, of carnage and blood-thirsty war songs. As we move through the Viking Age and beyond, they become more noble in their presentation, becoming more human, and losing their more supernatural duties. The sacrificial, ritualistic language practically vanishes, and they become defined by their protective nature more than anything else. Interestingly, they become more defined by their protective nature over individuals, or familial lines, not beholden to some great duty to reave death on hundreds. It’s a movement towards sanitisation and ‘domestication’, a sort of ‘saving what could be saved’ from the perspective of the Christian writer, while distancing elements that were seen as too emblematic of the old ways.

I’ll admit, in much of my previous work, I’ve been dedicating most of my attention to the first half of this timeline. I had more interest in exploring the almost demonic, feral appearance of the Valkyries in the earlier literary tradition as I wanted to see how the Vikings themselves may have seen or understood these beings, away from the metamorphosis nurtured by ante- and post-conversion writers and scholars.

Ultimately, I worship the Valkyries with an approach that takes all of these depictions into consideration – they are not a monolith, but individuals with agency and independence. With different roles and duties. The two perspectives aren’t mutually exclusive, and both of these depictions in my opinion play into their larger role of manipulating fate through and during battle. Whether that be enjoying the animalistic, blood thirsty nature of war, or through protecting specific individuals from the slaughter.

In the earlier traditions, they move around and across the battlefield clouded from human observation, and they are able to traverse our world and the world of the gods with few challenges. They can fly, have mounts that can fly, they can change their shape, and they can manipulate the battlefield in line with their choices. They deal in death, or protect individuals from death, or otherwise heal those who they decide are not to die.

So, how do the later Valkyries differ? Well, they are often tied to human relationships, whether that be through marriage, or through birth, often being identified as the daughters of kings. They don’t seem to ferry people to the halls of the afterlife, and they are almost exclusively based in ‘our world’, though with abilities that mark them as removed from normal humans. They are at least easily recognisable as being a Valkyrie, through what specific criteria we can only really guess at. Perhaps something that makes them seem to have an innate greatness – they’re often described as shining on horseback, after all. Bright and beautiful.

There’s a larger literary trope playing into all of this as well, the idea of our heroes quite literally courting death. Heroes are considered extraordinary due to exhibiting and doing extraordinary feats. The people around them are mythic and they are favourites of those that protect them, giving them an advantage over other individuals. The heroic lays are, in many ways, the stories of humans being elevated to almost godlike status, which is interesting when you compare what is happening on the other side of the coin. The gods, in turn, are being gradually stripped of their power. The Valkyries, I believe, are the natural middle ground here, considering that they have always been liminal and of both worlds throughout the timeline of their depictions. They are often made human by nature, but not by duty – albeit their power is reduced to protection over a handful of individuals, apparently.

One of the key examples of this is in Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar, with Sváva and the titular Helgi. Here we have a Valkyrie, Sváva, literally creating an identity and purpose for Helgi. He is taken from being utterly unknown to having a name and a duty of his own. A mission. Sváva then acts to protect Helgi during battle and build this reputation of being a keen warrior. He only dies when Sváva is absent, and a troll-woman curses him during a holmgang. But even then, the pieces are in place for an extraordinary resurrection of seemingly both Helgi and Sváva into Helgi Hundingsbane and Sigrun respectively. And Helgi firmly solidifies his position as a Nordic literary hero.

Apart from choosing the slain, the other aspect of the Valkyries that is often seen as archetypal of that position is to serve mead in Valhalla, but even here there is a lack of consistency when it comes to the sources. Ultimately, the Valkyries are not mentioned in every instance that we have mead being served in Valhalla. Today, the prominent academic paradigm is that this image of a Valkyrie mead bearer comes from the rather comic Eiríksmál which paints this image of a bumbling Odin being awoken and caught unawares at a new important arrival into his hall, and the Valkyries – these blood-thirsty battle goddesses – are painted, in turn, as mead bearers. There’s a satirical edge to it. As this piece is often dated to around 954, I see it as a key turning point to this transformation of the Valkyrie from one nature to another.

We don’t have mead-bearer Valkyries literarily speaking prior to Eiriksmál and indeed, that image isn’t even consistent afterwards. In Hákonarmál (and Snorri’s Heimskringla) we noticeably have the Aesir serving ale, despite Skogul and Gondul being present on the battlefield upon Haakon’s death. No Valkyrie is present when he arrives in Valhöll.

We’re then faced with the idea that Eiriksmál itself led to influencing much of the later depictions of this image, eventually tying into the domestication of the Valkyrie into the shape of wives and daughters. Continuing and complimenting the Christianised ideals of the role of women in society and thus the role of the Valkyrie. Luke John Murphy agrees with that sentiment and adds, “it seems likely that those Valkyrjur who are relegated to carrying cups or horns of alcohol do so as a result of an idealised vision of female behaviour in a hall as seen from the point of view of masculine warrior culture”. You can easily imagine how this image became reinforced over time, sitting nicely alongside the classical image of the Christian ‘angel’.

Saying all of that, I’m not necessarily against this image of the Valkyrie being a mead-bearer. Of course, to cherry-pick those instances as being ‘untrue’ to the image of the Valkyrie would be to draw an arbitrary line in the sand that chooses to ignore many of their attestations. Their evolution is part of their story and represents a fascinating journey through a transitional period in history. Equally, the mead-bearer aspects lend to interesting conclusions regarding the Valkyries’ use of rune magic, especially in the use of carving runes on drinking horns or otherwise brewing ale that offers the drinker supernatural power (referenced by Brynhildr to Sigurd in Volsungasaga). We also have Olrun, a Valkyrie whose name means ‘ale-rune’, hinting perhaps at some lingering association or tradition that has since been lost.

Taken holistically, we have several depictions of the Valkyries as blood thirsty demons of carnage on the battlefield, delighting in slaughter. We have a transitional period of blood-spattered protector and psychopomp, with a light peppering of a role of mead-bearer. Finally, we have an all too human, mortal protector with limited supernatural abilities, and no apparent role in ferrying the dead.

Putting these appearances together, the role of the Valkyrie takes on a two-pillared approach. A case of manipulating hundreds, if not thousands of lives on a battlefield, and nurturing and guiding those individuals who have the potential to change many lives in turn. We’re presented with a rather thorough approach to manipulating fate that extends beyond the idea of them simply choosing the slain in those that find themselves in their realm.

Finally, I firmly assert that by digging into who the Valkyries are – from both an academic and Heathen perspective – we can move into new discussions on the role of women in the Viking age, alongside the role of ‘supernatural femininities’. We’re in a time of re-evaluating archaeological evidence, and potentially starting to fill in holes in the literature that have long been glossed over.

The conversation is constantly evolving, and long-held ideas around various elements of what we believe in are being questioned and re-examined in new light. The Valkyries are complex and multifaceted. There’s something about them that remains massively evocative even to modern people, potent in the western zeitgeist. And I love them dearly, blood-spattered, viscera-covered, loom-made-of-body-parts-making, all.

[This piece was published on the Heathen Women United Facebook page for their ‘Women in Conflict’ theme for November 2023]

Bibliography

Bek-Pedersen, Karen. 2011. The Norns in Old Norse Mythology. Dunedin Academic Press, Scotland, UK.

Ellis, Hilda Roderick. 1943. The Road to Hel. Cambridge University Press.

Ellis Davidson, H.R. 1964. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Pelican, Harmondsworth.

Friðriksdóttir, Jóhanna Katrín. 2020. Valkyrie, the Women of the Viking World. Bloomsbury Academic. UK.

Murphy, Luke John. 2013. ‘Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age’

Price, Neil. 2002. The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia

Purser, Philip A. 2013. Her Syndan Wælcyrian: Illuminating the Form and Function of the Valkyrie-Figure in the Literature, Mythology, and Social Consciousness of Anglo-Saxon England. Dissertation, Georgia State University,.

Comments are closed